The Great Canadian Restart: How 2022 can spark an era of greener, more robust growth.

If 2021 was the year Canada rounded the corner on the pandemic recession, 2022 is the year it can accelerate out of a decades-long pattern of slowing growth.

Though a pandemic recovery is in sight, a slow-growing labor pool and lackluster record on investment and innovation have set a low-speed limit for the economy.

The greener, more digital, and tech-enabled society accelerated by COVID-19 has opened new pathways for growth that could ignite spending, investment, and innovation. Businesses and households are lined up to propel this change, but their efforts are likely to be hampered by near and long-standing obstacles.

As it starts its new mandate, the federal government can help set a new course. Growth-oriented federal and provincial government policies can be the foundation for the increased private investment needed to boost Canada’s growth trajectory.

Other countries are already remaking their economies in a bid to reverse the secular trend of low and declining economic growth rates. Canada does not want to be left behind. With a skilled workforce, strong record as a tech and energy innovator, and investment opportunities, it doesn’t have to be.

Source: Statistics Canada, Haver, RBC Economics

Source: Statistics Canada, Haver, RBC Economics

A 6 point plan for growth

1. Embrace new approaches to innovation policy

2. Forward-looking policy, public infrastructure and blended finance for climate action

3. Promote services trade and Canadian platforms; protect intellectual property and data

4. Increase competitiveness with tax, competition, and regulatory policy

5. Attract, develop and retain new sources of talent

6. Education and labour market policy for lifelong learning

Back to the starting line

GDP remains down compared to pre-pandemic levels, due to some particularly weak sectors. But many areas of the economy have already recovered or surpassed pre-pandemic levels. A mix of consumer spending approaching pre-pandemic levels, strong investment intentions, billions in business and household savings, and a supportive external environment will help fuel the ongoing recovery in 2022, even as firms continue to struggle with supply chain disruptions and a labour crunch. RBC forecasts growth of 4.7% in 2021, declining to 4.3% in 2022 and 2.6% in 2023 as it converges to its long-term trend

1.

With the end of the recovery—or cyclical growth—nearly upon us, we face a new question. Following the once in a century shock of the pandemic, how can we build more robust growth into Canada’s economy?

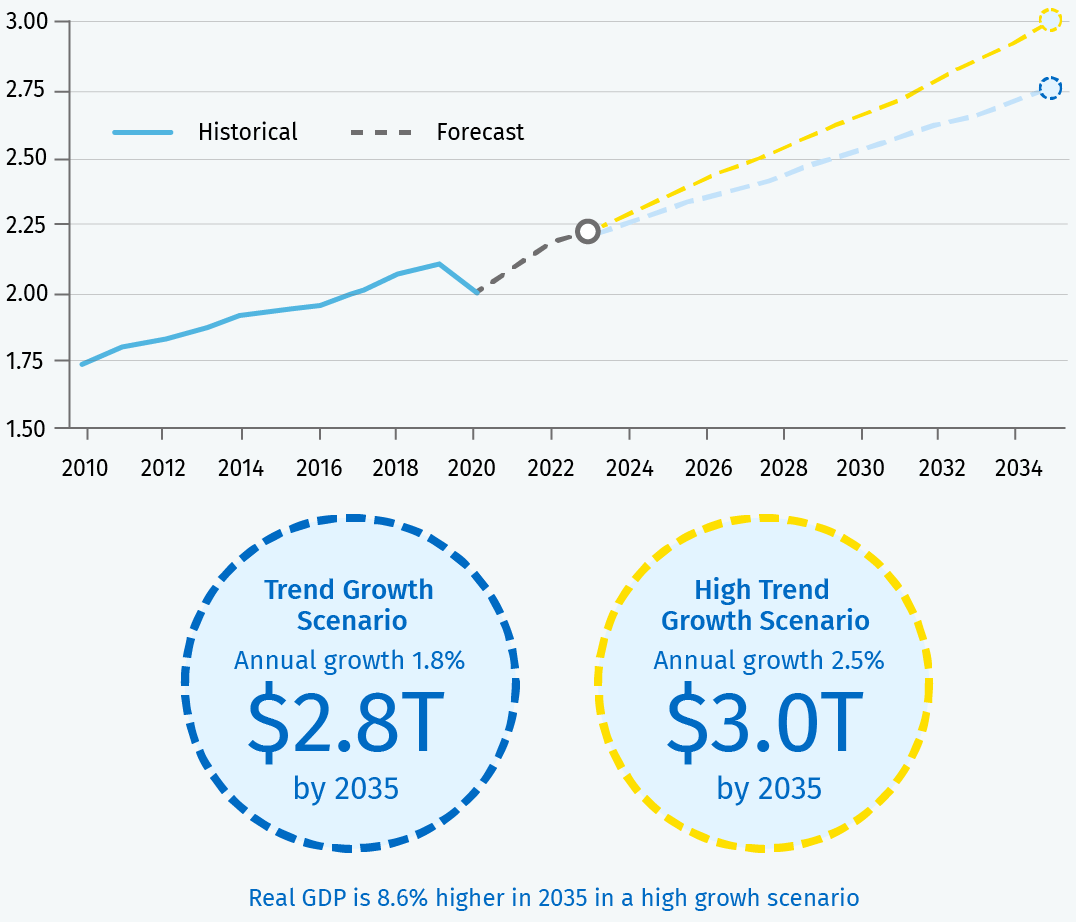

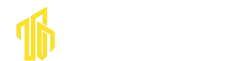

Over five decades, the country’s growth has been anything but dynamic. Real economic growth rates fell from an average of 4.1% in the 1970s to 2.1% between 2010 and 2019. Should we carry on our existing course, we expect a return to a sluggish trend growth of around 1.8% per year beyond 2023, a record reflective of slow labour force growth and muted productivity.

Canada isn’t alone. Many other advanced economies have experienced the same deceleration, attributed to a greying population, the slowing pace of innovation, and in some cases, post-recessionary economic scarring. The trend has been stubborn, suggesting that underlying structural issues will continue to be a powerful force now and into the future.

A new set of starting blocks

The next decade can be different. But if Canada is to secure a new growth trajectory, the private sector must take the lead. With an increase of $200 billion in the value of liquid assets since the start of the pandemic—and with long-term interest rates still low—corporate Canada has the muscle to do it.

There’s a business case for investment. Consumer surveys show a continued desire to engage with e-commerce. Canadians want to shop in a responsible way that favours local businesses and respects the climate and how employees are treated. And intensifying labour shortages provide a good reason to make production more efficient through new investments in automation and equipment.

Businesses’ investment intentions are up in recent surveys, with a majority saying capital expenditures over the next two to three years will be higher than before the pandemic. Many are focusing on digital investments.

It’s still too early to see a surge in business investment, but early evidence is encouraging: machinery and equipment (M&E) investment is above 2019 levels (excluding transportation equipment). Investments in research and development (R&D) and software are up, too. Trade data show a recovery in industrial machinery imports and a rise in imports of electronic and electrical equipment.

Increased digitization and automation should boost productivity, data and product development. And digitization—together with a greying population that tends to consume more services—can create opportunities for expanded services trade. Investment is needed for decarbonization, mitigation, and development of new green technologies. These same shifts in the global economy can bring opportunities for Canadian firms to export products and expertise, earning global incomes that can help fund the domestic adjustment to the new economy—one with greater spending, investment, innovation and growth.

Getting there will mean tackling new economy challenges, including changing sources of economic value that risk capital obsolescence and loss of competitiveness. It will mean responding to shifts in skills and jobs that threaten displaced workers, and inequality. It will also mean reckoning with where we have not performed well in the past.

Switching leads: Confronting a poor record on business investment and innovation

To achieve a materially different growth outlook, Canada needs to see a big shift in actual business investment and innovation.

Canada has a longstanding investment gap with peer economies. The C.D. Howe Institute finds that Canadian non-residential business investment per worker has lagged behind the U.S. since at least 1991 with the gap widening through the 90s, the mid-2010s and then again during the pandemic. By the second quarter of 2021, Canadian businesses invested 50 cents per worker for every dollar in the U.S

3.

The driver of Canada’s mid-decade underperformance was investment declines in the oil and gas sector shortly after the 2014 oil price shock. This investment, which is concentrated in non-residential structures, fell about 60% from its peak prior to the pandemic and remains weak. For the rest of the economy, the Canada-US investment gap stayed relatively stable, but the absolute gap is particularly high.

Canada has also seen a widening investment gap with the U.S. in machinery and equipment (M&E) and intellectual property (IP), driven in part by the oil and gas sector, but also weak M&E investment in other sectors. Investment in both M&E and IP stopped growing as a share of the economy after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

Canada has seen a declining GDP share of business investment in research and development, in contrast to many other OECD economies that have seen growing shares.

Given the lag in business investment, it’s not surprising that Canada has a labour productivity gap with the U.S. While the gap narrowed slightly post-GFC, by 2019, Canada produced just 74 cents per hour worked for every $1 in the U.S.

Meantime, lagging innovation could soon present an even greater problem. As technology advances, more economic value will be encapsulated in data, algorithms, brands, digital services and other ‘intangible assets’. With these assets being more scalable compared to tangible inputs like physical capital and labour, delivering large gains to its developers and owners, economic prosperity will increasingly depend on our transition to an innovation economy. And while innovation and competitiveness are influenced by many factors, from policy and demographics to the external environment, business investment is essential.

To varying degrees, Canada performs well in international rankings for entrepreneurial ambition, market sophistication, venture capital financing, institutions, and a skilled workforce. But it ranks poorly in other innovation inputs, with low business R&D investment, low adoption of information communications technology, low per capita scientific activity, an inadequate IP regime, and low openness to competition. And Canada has had trouble translating inputs to innovation outputs. It has middling patent activity, low business creation, and difficulty scaling businesses into global exporters. Firms that are able to export globally are a signal of economic competitiveness, yet net exports have been a drag on economic growth in Canada for much of the past two decades.

The result is imbalanced economic growth. When balanced, growth is derived from multiple sectors of the economy—consumption, investment, and net exports. For Canada, the imbalance between the low growth contribution from net exports and business investment on one side versus high contributions from consumption and housing on the other, means the economy is more exposed to individual economic shocks. For example, a shock to the housing sector could directly reduce economic growth through less construction and sales, and potentially force an abrupt, costly reallocation of resources to other sectors. With climate actions and trade tensions darkening prospects for Canada’s biggest export—crude oil—this imbalance could get worse.

New hurdles: Canada’s climate challenge

In addition to long-standing challenges, there are newer obstacles to unleashing spending and investment.

For one, firms that are trying to manage with higher pandemic debt levels, supplier challenges and labour shortages may struggle to plan for the future. Small businesses have historically lagged behind in digital adoption and the pandemic has further burdened seven in 10 of them with additional debt loads averaging $170,000.

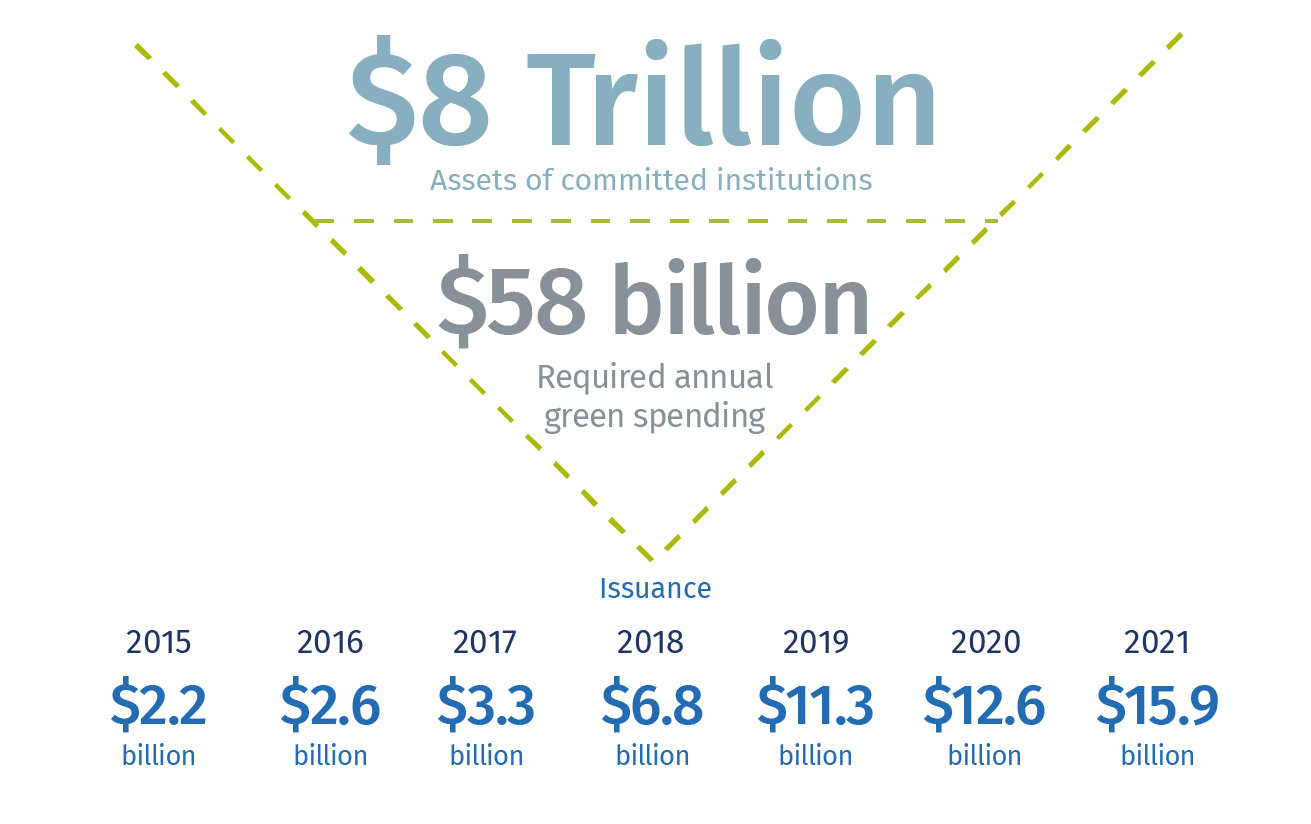

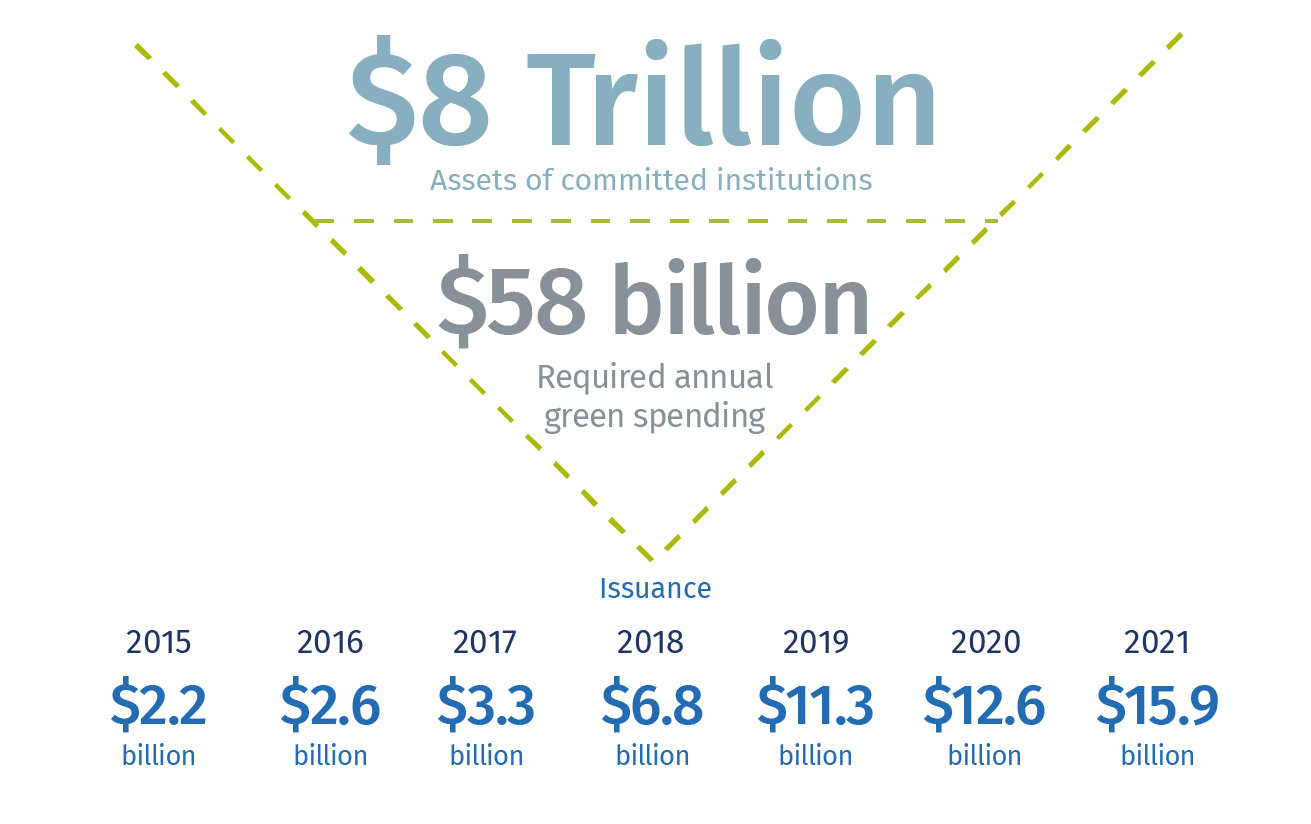

There are also impediments to connecting huge climate funding commitments to green projects. Large Canadian firms with $8 trillion in global assets have committed to Net Zero by 2050, yet spending on green projects is still much lower than the $60 billion per year we estimate that Canada needs to reach.

Only 6% of Canadian firms plan to measure their environmental footprint over the next year, including less than 25% of large firms with 100+ employees.

And while the pandemic, a lack of financial resources, and clients not willing to pay a higher price are sometimes identified as hurdles to adopting green practices, the majority of businesses identified no challenges.

Source: Bloomberg, RBC Economics | *data to November 1, 2021

Source: Bloomberg, RBC Economics | *data to November 1, 2021

The outcome for growth will also depend on supply. If the supply of finance is not a challenge, the availability of some goods may be. As much of the global economy edges toward a green, digital and tech-equipped society, there will be greater demand for the goods that facilitate it—5G networks and cybersecurity systems, critical minerals, batteries, EVs, and renewables. Meeting this demand will take time. Semiconductor factories and lithium mines can take a decade to develop. And the increasingly nationalist agendas pursued by many countries may reduce access to these competitive resources.

Yet it’s another, more localized supply constraint that may pose the most significant challenges.

The lynchpin: Human capital

Canada needs people and skills to reshape the economy. But population ageing and the changing nature of work threaten disruptions in labour markets that could become a significant drag on growth. These are not future problems. The economy was already grappling with labour shortages that have only been accelerated by the COVID-19 crisis. Pandemic-delayed retirements have created a potential wave of workforce exits in the year ahead and immigration levels have still not recovered. This is reflected in a third of businesses reporting labour shortages and a high national job vacancy rate of 6%.

These labour shortages will intensify. Population ageing has led to a declining labour force participation rate, which has subtracted about 1 million people from the workforce since its peak, and represented a drag on economic growth since 2010, when the first baby boomers turned 65.

The participation rate is projected to decline further over the next 15 years and could mean an additional 1.5 million fewer workers over that period, including up to 600,000 over the next three years.

Higher government immigration targets, if met, would address the pandemic immigration shortfall and help boost the number of available workers. But it won’t be enough. To keep the age structure of the population constant at 2020 levels, the annual immigration targets would have to double.

Getting everyone in the race: Canada must tap its rich supply of human capital

Large pools of talent remain underutilized in Canada. Closing the women’s participation rate gap would add another 1.2 million people to the labour force. And other segments of the labour force have been underemployed relative to their credentials. Closing the visible minority earnings could lift GDP by nearly $30 billion per year

7, and while not additive because of overlapping populations, closing the immigrant employment and wage gap has the potential to add $50 billion per year in GDP. Indigenous Canadians are also a significant source of untapped potential, particularly given they are the fastest growing youth population.

Having the right number of workers is key, but skills are just as important. If graduating youth are equipped with new skills and starting in new fields, the impact of potential displaced workers could be minimized. But some educational programs are not keeping pace with change, access to work integrated learning can be uneven, and young people can struggle to get hold of the information they need to make career choices. Despite greater demands, post-secondary institutions face a constrained funding model with tuition freezes and reliance on high-paying international students.

Mid-career workers face different challenges. While tight labour markets should incentivize more business spending on employee training, low wage workers whose jobs are more likely to be affected by automation, and who could benefit the most from upskilling, are also the least likely to participate in it.

Competing for the workforce of the future

A skilled labour force, world-class educational institutions, and an open immigration system give Canada an edge in the global race for talent. But Canada is not the only country struggling with an aging population. Other countries are also looking for highly-skilled immigrants to build their clean and knowledge-based economies.

International firms are using new remote work options to recruit international tech talent. Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Netflix have made plans to aggressively recruit in Canada this year. And while resident Canadians earning Silicon Valley wages may be good for the local economy, it could also be a growth-limiter for Canadian firms if they cannot compete in the international skilled labour market.

Canada’s high housing prices could be a challenge: about 60% of Canada’s permanent residents end up in Toronto, Vancouver, or Montreal, yet two out of three of these cities have among the highest housing costs in the world measured against median incomes

9. House prices are even challenging for higher-earning workers. Remote work may help with this, but knowledge-based workers may still be drawn to cities.

Setting the course: The government needs a growth-oriented agenda

To avoid missing out on investment, innovation and talent, Canada must take a closer look at the overall policy framework. Specifically, structural policy—tax, regulation, competition, infrastructure, education, innovation, and trade policy—must work in concert with sectoral strategies and government spending programs to address the challenges before us.

Governments have spent a lot on income support and other programs since the start of the pandemic—an estimated additional ~$400 billion in program expenses over two years (a 50% increase) just at the federal level—preventing long-term scarring to labour markets and balance sheets. Now, their focus has turned to ‘recovery funding’ directed at still-struggling sectors and a range of economic and social issues. Some of this isn’t temporary. Governments have introduced major structural spending programs and, at least at the federal level, signs are any ‘fiscal space’ will be used to expand spending.

This doesn’t need to be a bad thing for economic growth. Social infrastructure like health care, community services and public housing enable individuals to participate in the economy. The pandemic helped shift the policy lens to varying health and economic outcomes, including longstanding equity gaps. Inequality, particularly at high levels, can impede economic growth through insufficient human capital development, weaker consumption or political instability.

And, there is greater recognition that more expansive fiscal policy could be important to breaking free from a low growth economy. Many economists believe that inadequate government spending held back the post-GFC recoveries in the U.S. and Europe. Given the relatively sanguine attitude of bond markets to high government deficits in advanced economies, and low interest rates, governments seem to have more fiscal firepower than they previously thought. Several global economies are experimenting with higher levels of deficit-financed public spending to spur spending, investment and growth.

But these relationships aren’t guaranteed, especially if social spending only finances current consumption, doesn’t target the largest equity gaps, or discourages employment. And financing government programs with a deficit comes with a risk: the new spending might not lead to sufficient economic growth to address future interest rate increases or other economic shocks.

Canada needs a focused, growth-oriented fiscal program to balance these risks. Targeted and forward-looking government policies can be the foundation for increased private investment that tilts Canada’s growth trajectory.

A six-point growth plan

The challenges may be clear, but the solutions are less so. Past policies have struggled to change the course. The increasingly green, knowledge and services-based economy could represent a new growth trajectory for Canada, but it needs a push.

There’s no single policy solution. Canada needs to confront the big challenges of the new economy, like climate policy, IP framework, and skills strategy, and realign the longstanding policy frameworks of the old one, including tax, competition and regulatory policy.

A growth-focused government strategy would encourage increased capital investment in technology and process innovation, helping Canadian firms scale to global markets. It would also enhance outcomes for Canadians in untapped talent pools, promote systems of lifelong learning, and support labour market transitions.

1. Embrace new approaches to innovation policy

Canada’s poor performance on business R&D investment has persisted in spite of above-average government support. Its approach to innovation—providing support through the tax system skewed heavily towards small and medium-sized firms—may be a barrier to innovation output and scale. Meantime, the U.S. and other countries are increasingly pursuing strategies to build economic capacity and compete for geopolitical dominance in new industries.

10

Canada should test alternative innovation policies, including providing more support within core programs for larger, growth-oriented firms. More focused, de-politicized and resourced industrial strategies focusing on green and advanced technologies within North American supply chains may de-risk projects and draw private capital. Government procurement and targeted business supports may also accelerate technology adoption.

2. Forward-looking policy, public infrastructure and blended finance for climate action

The gap between green financing commitments and investments—and emissions targets and emissions—reflect a lack of projects with clear financial returns. Given the long time horizon, uncertainty is high around paths to decarbonization and underlying technology costs. Smaller markets for greener products mean firms may not be able to pass on abatement costs to their customers, challenging competitiveness for those that cut emissions.

Governments could prompt more climate action. Carbon pricing should continue to be a key pillar of the plan, rising predictably and applying more broadly. Hard infrastructure like EV-charging networks and carbon pipelines can help make it easier for households and firms to invest in emissions cuts. Canada should push for international cooperation on border carbon adjustments to protect domestic industry while furthering international progress on climate goals. Policy strategies can lay out a clear pathway for individual sectors, from oil and gas to agriculture, and promote blended finance pools of public, private and Indigenous capital for the early stage technologies we may need by 2050.

3. Promote services trade and Canadian platforms; protect intellectual property and data

Canada is a net exporter of R&D services and also a net importer of IP, suggesting Canada is not retaining ownership of its IP and is instead leasing it back from foreign companies. And foreign tech companies are monetizing Canadian data assets. With scalable, intangible assets driving tremendous value, this could be a missed opportunity to drive the scaling of Canadian firms and services exports. A broad range of services, from health care to software to the digital services embedded in the Internet-of-Things, are primed for growth.

Canada needs to consider forging trade agreements that address barriers to expanded global services trade. It needs to review its intellectual property regime to incentivize IP retention and outline data rights. Global platforms should be taxed at the same level as Canadian intermediaries, while multinationals should see time limits on tax benefits, with public money focused on local procurement over employment. Policy can support the development of Canadian platforms featuring local commerce, education and travel.

4. Increase competitiveness with tax, competition, and regulatory policy

Expectations of more public spending are raising concerns over future tax increases and creating uncertainty that may be limiting investment. Canada’s tax system has not been reviewed since 1967, and deviates in important ways from core tax policy principles like efficiency and simplicity. Canada’s low international rank in openness to foreign direct investment could be holding back innovation, while interprovincial trade barriers may be subtracting up to 3.8% from the economy per year.

11

Canada should undertake a tax policy review to streamline tax expenditures, ensure competitive rates of personal taxation (including for international skilled talent), encourage more public-private investment, incentivize re-investment and longer investment horizons, and target tax supports for newer and growth-oriented firms. Regulatory policy, especially in the context of interprovincial trade, also needs attention.

5. Attract, develop and retain new sources of talent

Affordable childcare and flexible working hours have long been identified as major barriers to women’s participation in the workforce. Meantime, challenges in integrating newcomers into labour markets, and opportunity gaps for Indigenous and some visible minority groups, have left other rich sources of workers underutilized.

National child care can have a big impact by targeting the largest affordability and accessibility gaps, while national standards within the early learning system can help expand the next generation of talent. Making the higher annual immigration target of ~1% population permanent, updating special visa programs with a more forward-looking assessment of labour market gaps, recognizing foreign credentials and providing greater pre-arrival labour market support can increase the participation of immigrants. Underrepresented groups should be encouraged to develop new green and digital skills.

And good housing market policy is good labour market policy. Governments of all levels need to coordinate a systematic review of housing policy to address supply-side constraints, rationalize demand-side policies, address inequality, and ensure financial and economic stability.

6. Education and labour market policy for lifelong learning

Despite a relatively high share of adults participating in on-the-job training, Canada has some of the largest participation gaps in the OECD.

12 Workers who are highly-skilled, of prime-age (25 to 54 years) and employees of larger firms are most likely to get training.

Canada should explore redesigning income support programs to enable more reskilling while working. Policy makers should update the skills strategy and Canada Training Benefit for green skills and explore national tuition standards to balance access and revenue needs. Provinces should study rapid reskilling programs in various sectors to scale what works, accelerate the incorporation of skilled trades and digital and coding skills into their K-12 curriculums, and provide support for collaborative approaches and common platforms for helping small and medium-sized employers better prepare for their skill and training needs.

Canada’s immigration boost could fuel hot housing market: experts.

By Steve Scherer and Julie Gordon – December 9, 2021

Canada hopes more immigration can boost economic growth and allay a worsening post-pandemic labor shortage, but new migrants could pour gasoline on that red-hot housing market that the central bank has warned was stoked by “a sudden influx of investors.”

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s administration is on track to meet this year’s goal of 401,000 new permanent residents and is set to revise up next year’s target of 411,000, a government source said.

Canada’s successive governments have relied on immigration to drive economic growth in the face of a declining fertility rate, which hit a record low last year. With the pandemic triggering early retirements among aging Canadians, attracting immigrants has grown more important. Also, the country targets high-skilled immigrants who tend bring in money and earn enough to compete for desirable housing.

“Canada needs immigration to create jobs and drive our economic recovery,” Immigration Minister Sean Fraser told Reuters. “It’s not just that one in three Canadian businesses are owned by an immigrant, but also that newcomers are helping to tackle labor shortages.”

Housing costs have surged due largely to low interest rates and a supply shortage. Migration was another factor, especially pre-pandemic. Now that most borders are open again, more newcomers are likely.

Housing prices have helped stoked inflation to its highest in 18 years. Government plans to mitigate housing costs will take time to put in place, and some measures may further strengthen demand, economists say.

“It is a conundrum,” said Stephen Brown, senior Canada economist at Capital Economics, said of the effect of immigration on housing costs.

Still, ongoing construction and the need for labor justify more immigration. Canada has reached a point where the labor force will “flatline” without immigration, Brown said.

Job vacancies in Canada have doubled so far this year, official data shows. The association of Canadian Manufacturers & Exporters is asking the government to double its target for economic class immigrants by 2030 because of worker shortage in manufacturing.

The benchmark home price is up 77.2% since November 2015, when Trudeau took power. His government plans to present a housing package to the parliament, including a C$4 billion ($3.2 billion) fund for the country’s largest cities to accelerate housing plans.

According to Statistics Canada, immigrants tend to buy in large urban centers, like greater Toronto and Vancouver, where home prices are now above C$1.12 million. Nationwide, a typical home now costs C$762,500 ($600,299), realtor data shows. The value of a typical home in the United States is $312,728, according to Zillow.

Rapid price gains are set to slow next year, though analysts polled by Reuters still see Canadian home prices rising 5.0% in 2022, making them less affordable.

The aim of the government fund is to create 100,000 new “middle-class” homes by 2024-25 and the cash will go to municipalities that show they can speed up construction.

Economists say this measure could be helpful, but they do not like some other measures in the housing package because they would increase demand even more.

Prior to the pandemic, the Peel region – part of the Greater Toronto Area – was welcoming some 45,000 newcomers each year, but that stopped during the pandemic because of border closures, said real estate broker Jodi Gilmour.

“Right now we are seeing a rush of buyers trying to beat the two things that are going to change their position going into 2022, which are rising interest rates and competition from immigrants,” she said.

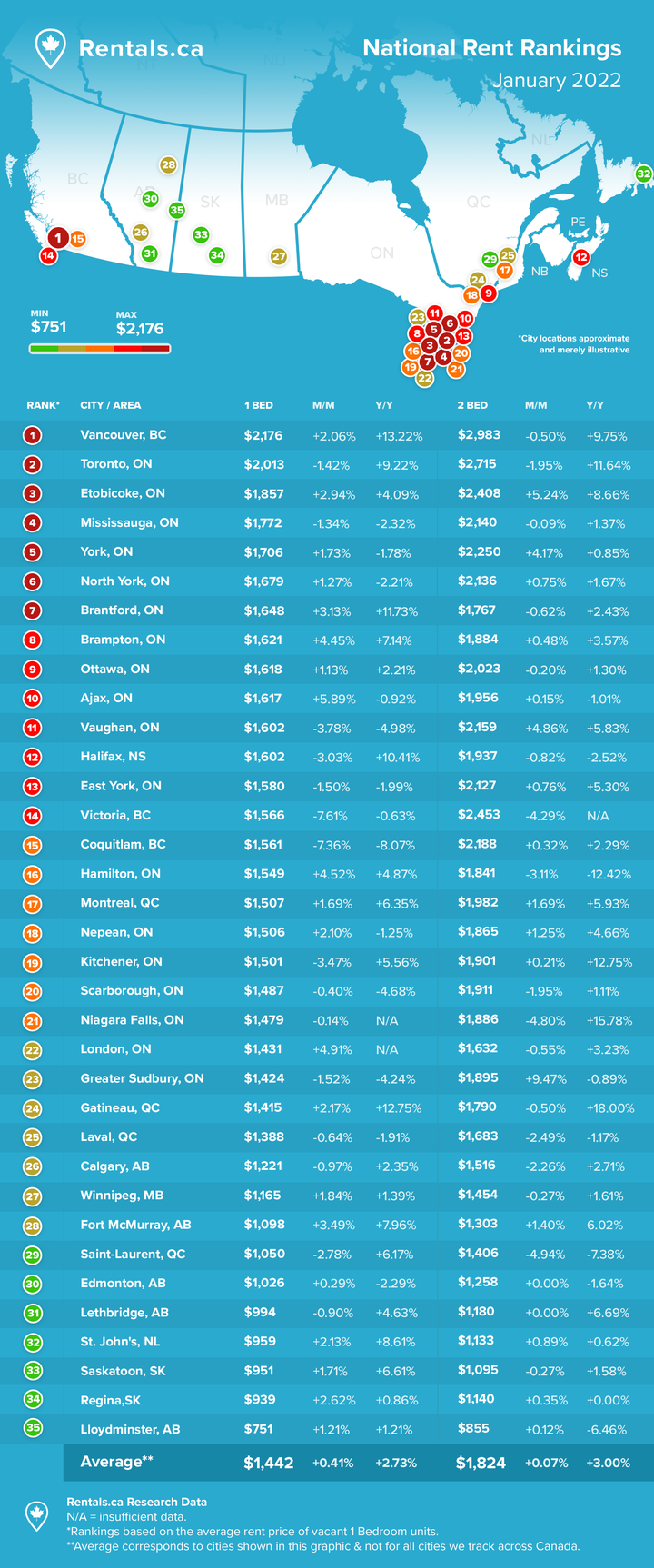

Rentals.ca January 2022 Rent Report.

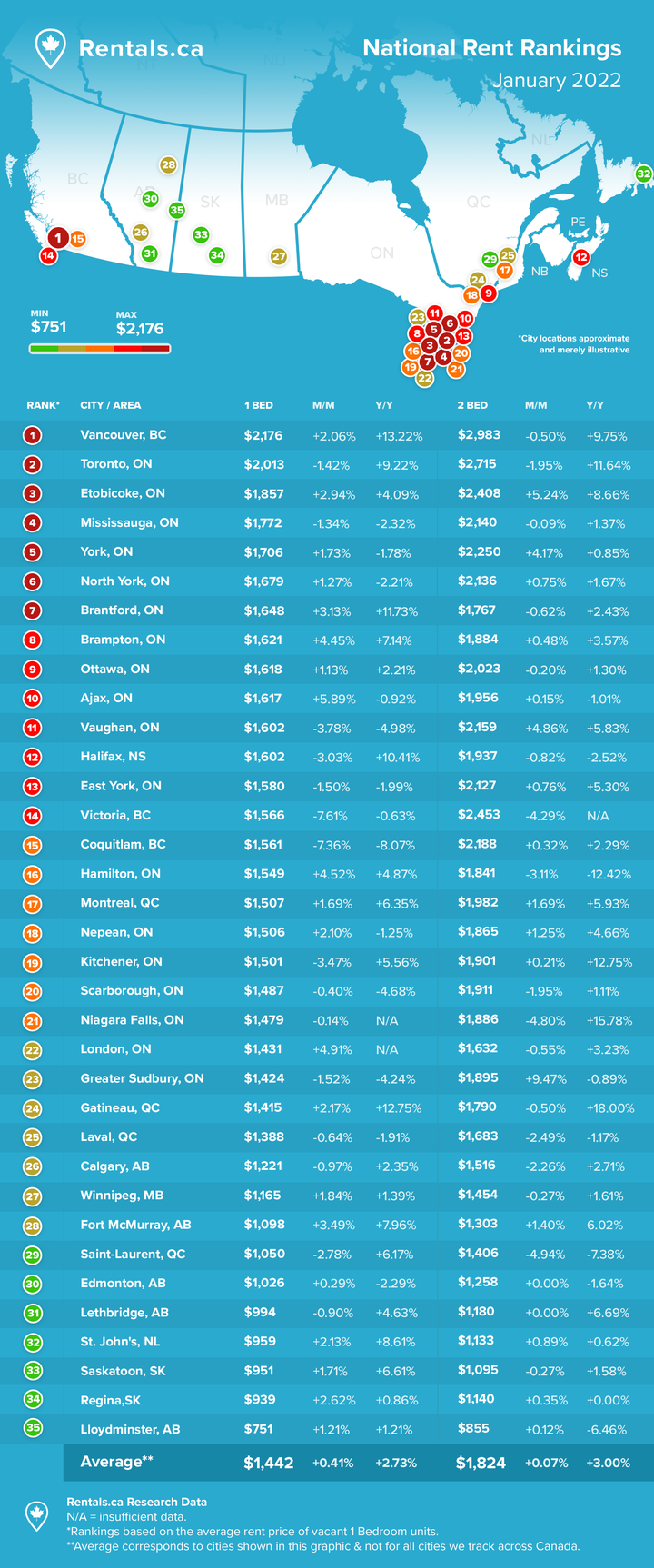

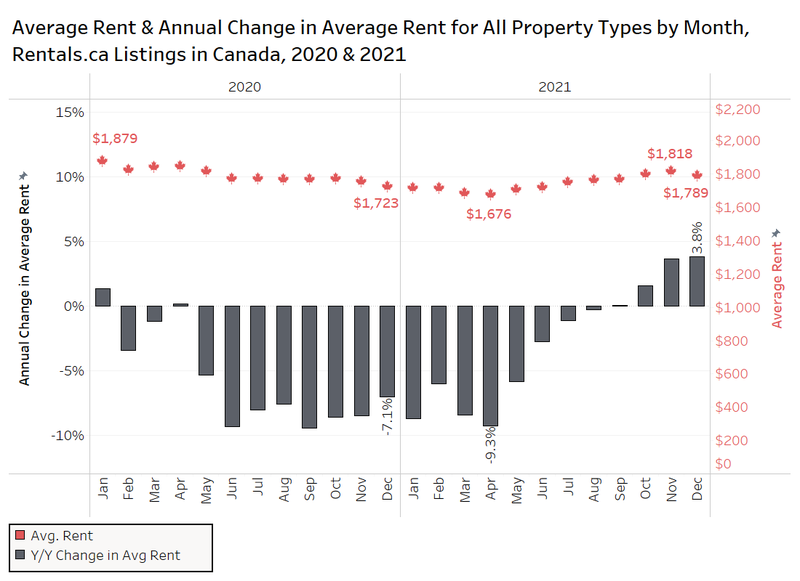

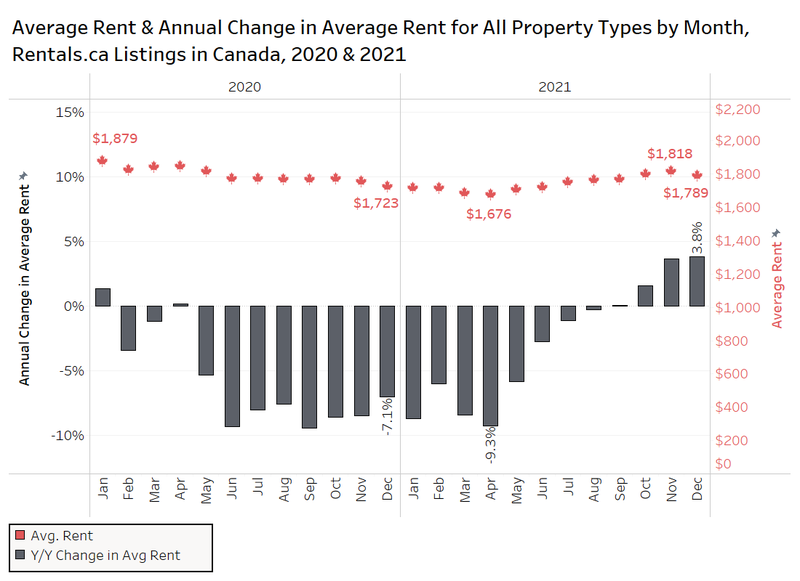

The average rent for all Canadian properties listed on Rentals.ca in December was $1,789 per month, up 3.8% annually. This is the fourth consecutive month with a positive annual change in average rent following 16 consecutive months of decline.

National Overview

The average monthly asking rent for all property types in Canada, including single-family housing, townhouses, rental apartments, condominium apartments, and basement apartments cumulatively from January 2020 to December 2021 is shown in the chart below (red). The annual change in average rent is represented by the grey bars. This data is generated from Rentals.ca listings data.

However, for the first time since April, the average rent decreased month over month, falling 1.5% from $1,818 per month in November. Rental rates tend to fall in December as prospective tenants are concentrating on the holidays and not looking for apartments. It is not likely that the Omicron virus was the culprit, as average rents declined 1.8% monthly in December 2020, and 3.3% monthly in December 2019.

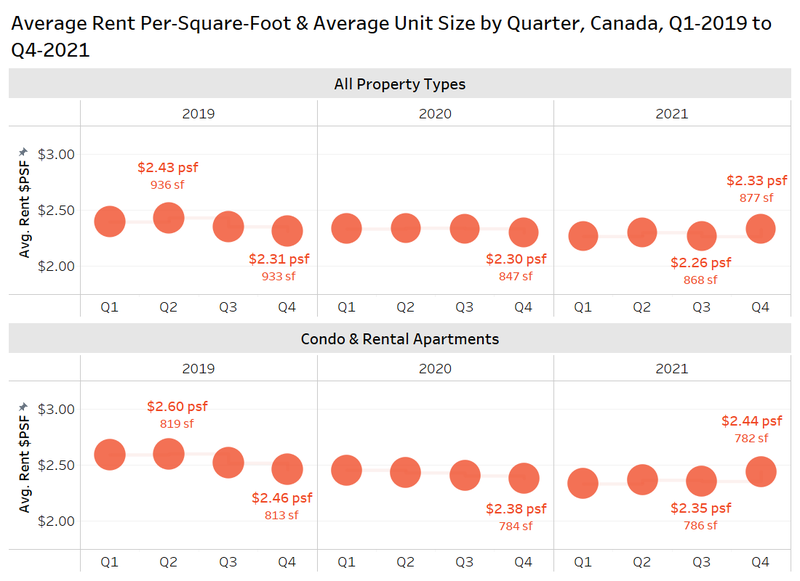

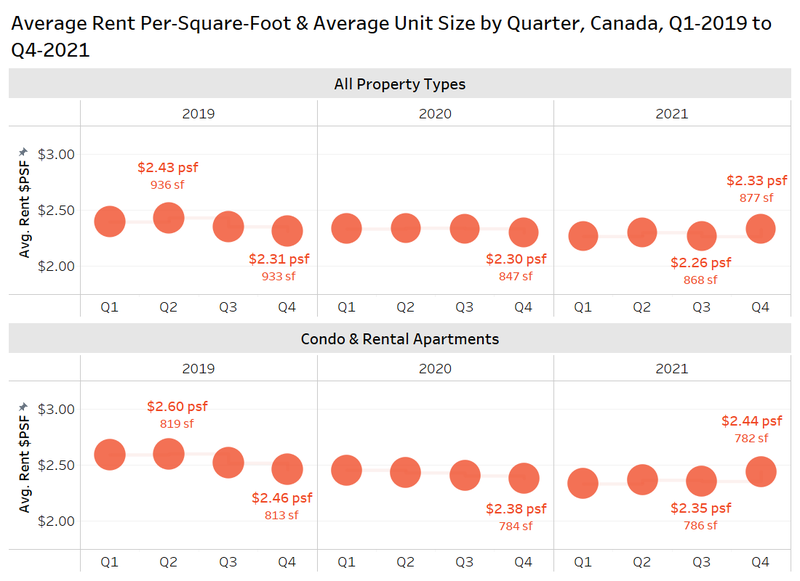

National Rental Rates Per-Square-Foot and Quarter

The chart below shows the average rent per-square-foot for all property types in Canada by quarter via Rentals.ca listings data over the past two years (top panel). Also shown is the average rent per-square-foot for condo and rental apartments only by quarter (bottom panel). Not all listings make their unit size available, and those that do tend to skew toward newer properties, thus making the figure likely higher than it would be with a more comprehensive sample.

The average rent per-square-foot for all property types was $2.33 on average in Canada in Q4-2021, an increase of 1.3% annually from the Q4-2020 average of $2.30. The average listing was 877 square feet in the fourth quarter of 2021 versus 847 in Q4-2020. Over the past three years, the market peaked at $2.43 per-square-foot in Q2-2019.

The average rent per-square-foot for condo and rental apartments in Q4-2021 was $2.44, which was an annual increase of 2.5% from the Q4-2020 average of $2.38. The average unit size was virtually unchanged year over year at 782 square feet in Q4-2021 versus 784 square feet a year earlier. Over the last three years, the market peak was Q2-2019 at $2.60 per-square-foot, where the average size was larger at 819 square feet.

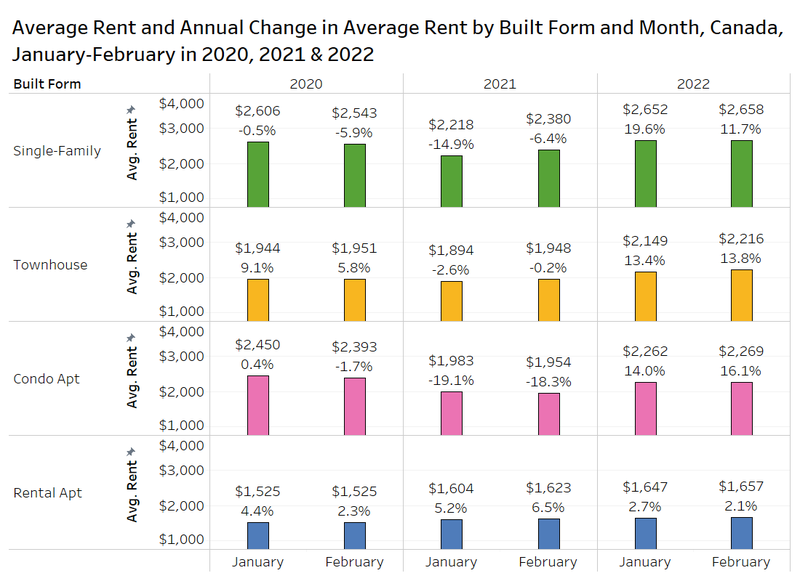

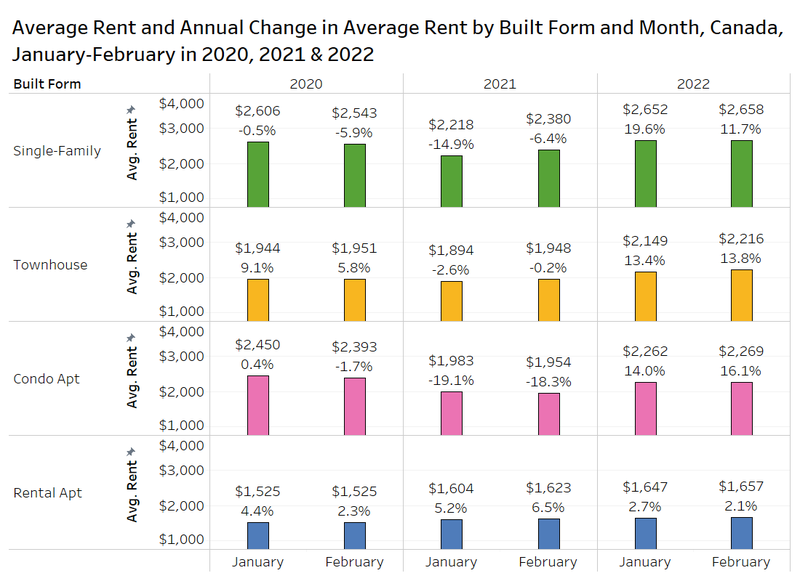

Rental Rates by Property Type

The next figure presents data on the average monthly rent, average rent per-square-foot and median rent for single-family properties (single-detached and semi-detached houses), condominium apartments, and rental apartments in Canada via Rentals.ca listings in November and December in each of the last four years.

The average single-family home was offered at $2,546 per month in December 2018, rising 2.2% to just over $2,600 in December 2019. The average rent declined 9.3% in the pandemic-impacted 2020 to $2,360, despite the fact that the average rent per-square-foot was unchanged at $1.66. In December 2021, the average rent for a single-family home was $2,570 per month – an annual increase of 8.9%, but still below pre-COVID-19 highs. However, the average rent per-square-foot declined 6% in December 2021 to $1.56, which reflects the changing composition of single-family listings, which can range from a 900-square-foot bungalow on a small urban lot to a 7,000-square-foot home on a multi-acre lot in a rural setting.

Condominium apartments experienced an annual increase of 11% to $2,227 per month in December 2021. The average rent per-square-foot also experienced an annual increase of 6.9% to $2.96 in December 2021. Condos were hit the hardest during the early pandemic period as some tenants fled the big cities and their expensive housing, with condo rents falling by a whopping 18% annually in December 2020.

Apartments have not experienced the same levels of increases as single-family homes and condo apartments, moving from $1,603 per month in December 2020 to $1,623 per month in December 2021 (an annual increase of just over 1%). The average rent per-square-foot has experienced an annual increase of 4%, moving from $2.20 in December 2020 to $2.29 in December 2021.

Unlike singles and condos, apartments did not experience rent declines in 2020. This likely has to do with more incentives being offered by apartment landlords, like one or two months of free rent, while the landlords and investors who own single-family homes and condos for rent were more likely to simply lower the rent. Secondly, there were a number of new purpose-built rental apartment completions in several cities in 2020, and the slower absorption and lease-up at these projects resulted in these new and expensive apartments having listings on Rentals.ca for longer than normal, giving the impression that average rents were higher.

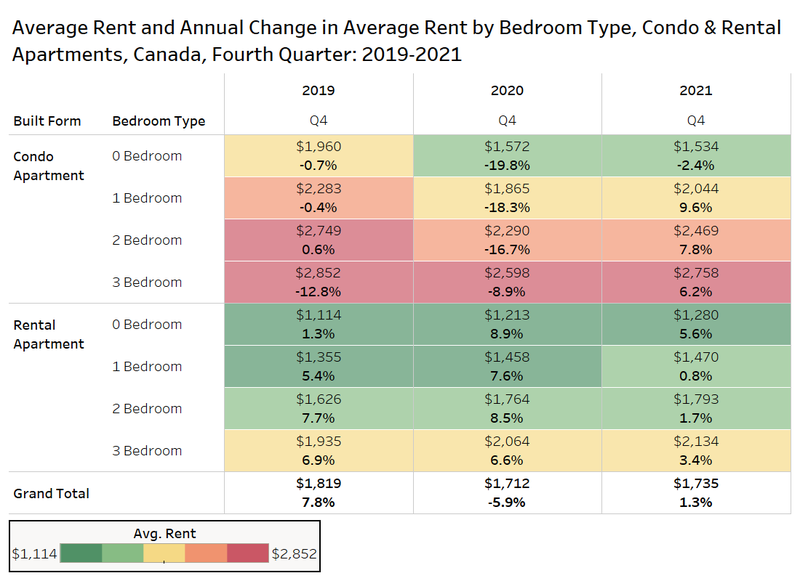

Rental Rates by Bedroom Type and Property Type

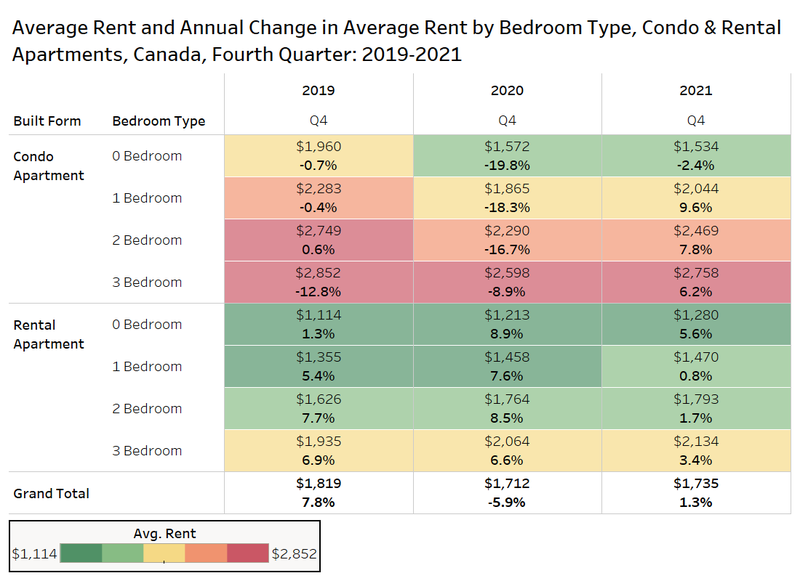

The chart below looks at the average rent and annual change in average rent in the fourth quarter of 2019, 2020 and 2021 for condominium and apartment rental properties nationally.

Overall, the average rent for these two property types combined experienced a slight annual increase of 1.3%, moving from $1,712 per month in Q4-2020 to $1,735 per month in Q4-2021.

For condo apartments, the average rent for a studio unit experienced an annual decline of 2.4% to $1,534 per month in Q4-2021. This is the only bedroom type that experienced an annual decrease in monthly rental rates. One-bedroom condo apartments experienced an annual increase of 9.6% to $2,044 per month; two-bedroom condo apartments experienced an annual increase of 7.8% to $2,469 per month; and three-bedroom condo apartments experienced an annual increase of 6.2% to $2,758 per month. All of the condo bedroom types remain well below Q4-2019 rent levels.

For rental apartments, studio units experienced the highest year-over-year rise by bedroom type with an annual increase of 5.6% to $1,280 per month in Q4-2021. One-bedroom units experienced an annual increase of 0.8% to $1,470 per month; two-bedroom units experienced an annual increase of 1.7% to $1,793 per month; and three-bedroom units experienced an annual increase of 3.4% to $2,134 per month. All bedroom types for rental apartments increased annually in 2020 and 2021.

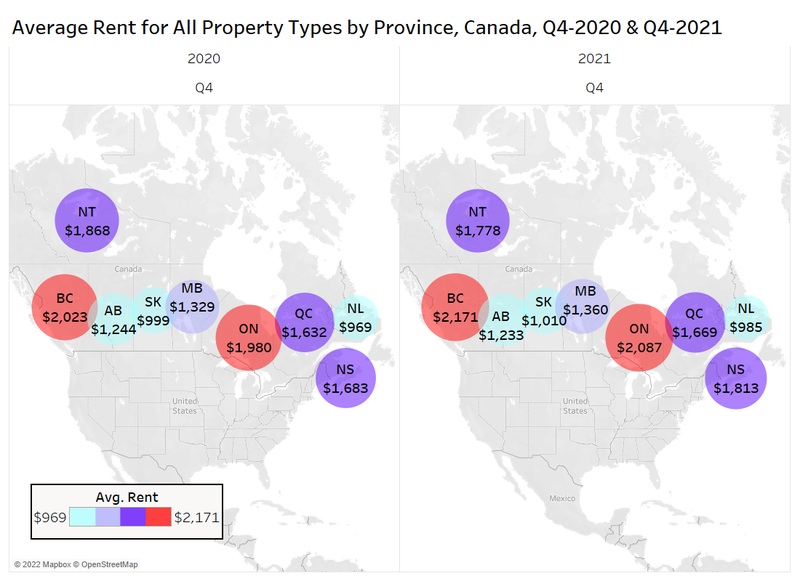

Provincial Rental Rates

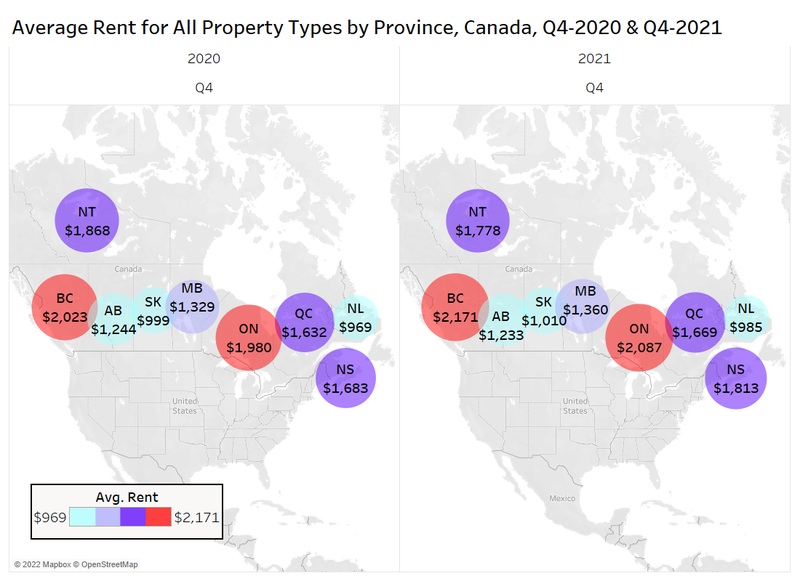

The chart below looks at the average rent for all property types by province in Q4-2020 and Q4-2021.

The average rent in British Columbia was up 7.3% annually in 2021 to $2,171 per month. Ontario’s rent increased annually by 5.4% to $2,087 per month.

The average rent in Nova Scotia moved from $1,683 per month to $1,813 per month – an annual increase of 7.7%. Anecdotally, it has been reported there has been an influx of Ontario residents moving to Nova Scotia since the pandemic started, driving up rental rates there.

The Northwest Territories experienced an annual decline of 4.8% to $1,778 per month as the only province that experienced any notable annual decreases in average rent, however, the sample size of listings is small. The average rent in Alberta moved from $1,244 per month in Q4-2020 to $1,233 per month in Q4-2021 — an annual decline of less than 1%.

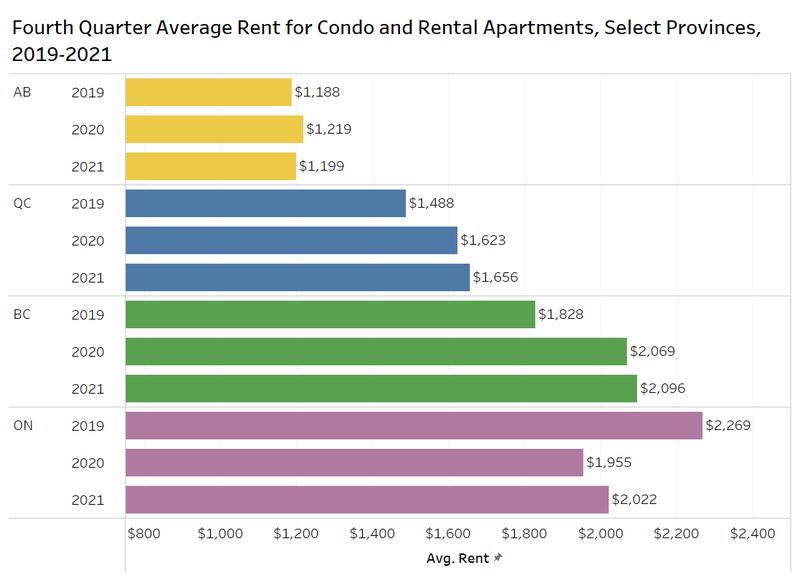

Average Rent for Condo and Rental Apartments in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario and Quebec

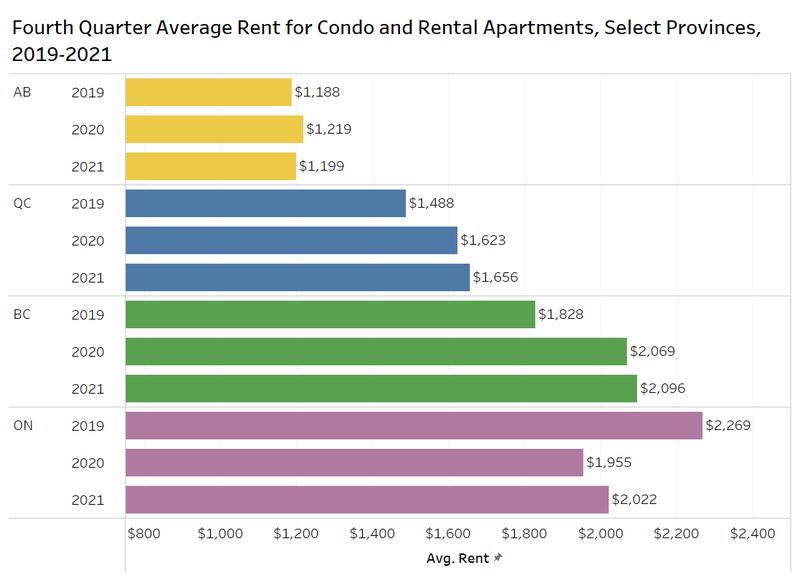

The chart below looks at the average rent in the fourth quarter in 2019, 2020 and 2021 for condo and rental apartments in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario and Quebec based on listings data from Rentals.ca.

The average rent in Alberta has more or less remained unchanged since 2019, moving from $1,188 per month in 2019, to $1,219 per month in 2020, to $1,199 per month in 2021.

Quebec has seen its average rent move from $1,488 per month in 2019, to $1,623 per month in 2020, to $1,656 per month in 2021. This represents an annual increase of 2% in Q4-2021.

In British Columbia, the average rent for condo and rental apartments moved from $1,828 per month in Q4-2019 to $2,069 per month in Q4-2020, which represented an annual increase of 13%. In Q4-2021, the average rent experienced minimal change, moving from $2,069 per month in Q4-2020 to $2,096 per month in Q4-2021.

In Ontario, the average rent experienced a sharp decline from $2,269 per month in Q4-2019 to $1,955 per month in Q4-2020. This represented an annual decrease of 14%. In relation to the other selected provinces, the average rent in Ontario increased at a higher rate in 2021, moving from $1,955 per month in Q4-2020 to $2,022 per month in Q4-2021 (an annual increase of 3.4%).

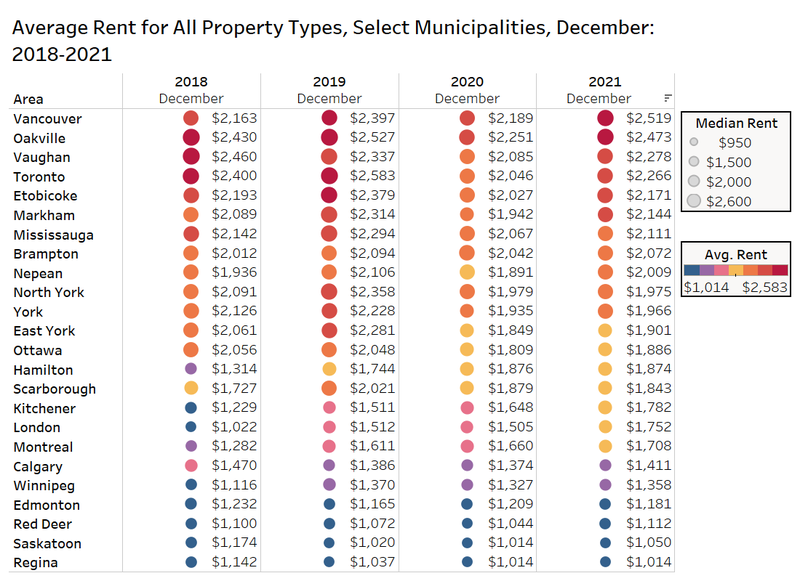

Municipal Rental Rates

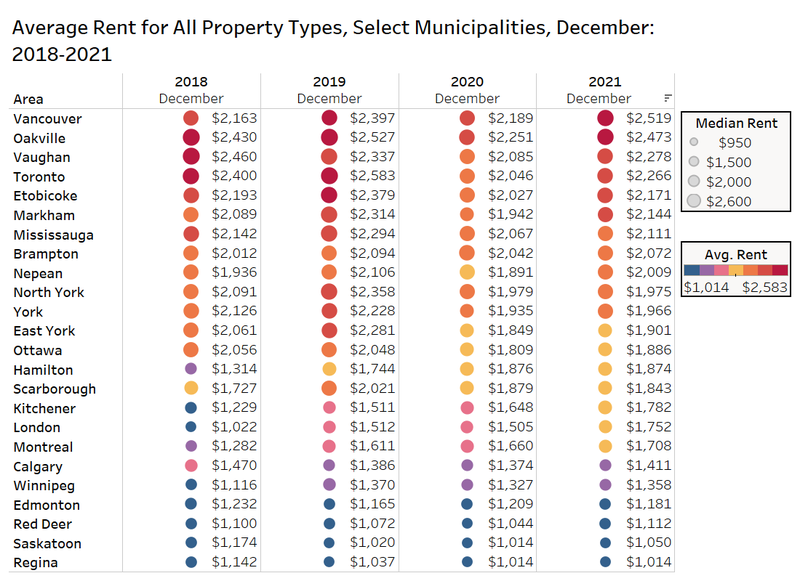

The chart below looks at the average rent for all property types for December in each of the last four years for select municipalities in Canada (and former municipalities prior to amalgamation in Toronto).

The majority of the selected municipalities experienced an increase in average rent moving from December 2020 to December 2021. North York, Scarborough, Hamilton, and Edmonton were the only municipalities that experienced a decline in average rent (which were minimal).

Vancouver had the highest average rent in December 2021 among these municipalities and former municipalities at $2,519 per month, which is an annual increase of 15% from the December 2020 average of $2,189 per month. Oakville had the next highest average rent at $2,473 per month – an annual increase of 9.9% from its December 2020 average of $2,251 per month. The lowest average rent out of the select municipalities was found in Regina with an average of $1,014 per month, which had remained unchanged since the previous year.

Bullpen Research & Consulting and Rentals.ca’s forecasts from the previous year were fairly close for Calgary, Mississauga, Montreal, and Toronto, with average rents in the select municipalities landing within $150 of the averages forecasted. The average rent in Vancouver was $2,519 per month in December 2021, which was much higher than the predicted average of $2,240 per month.

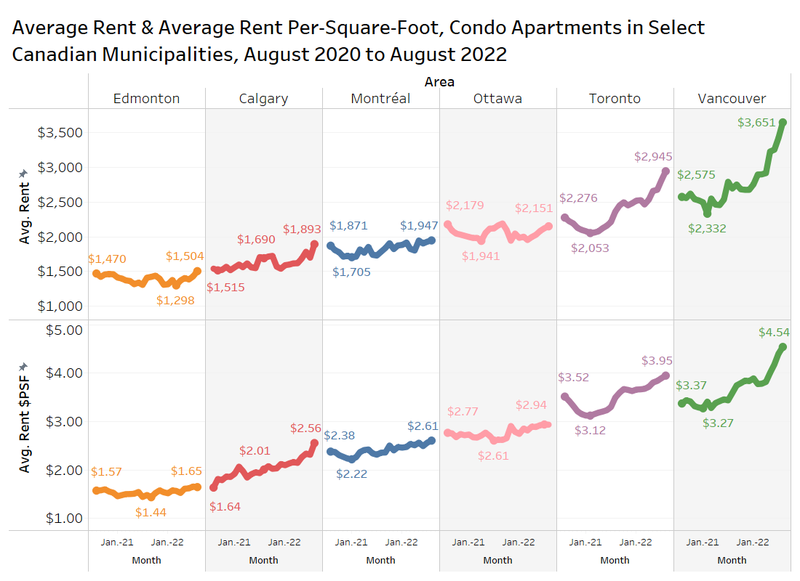

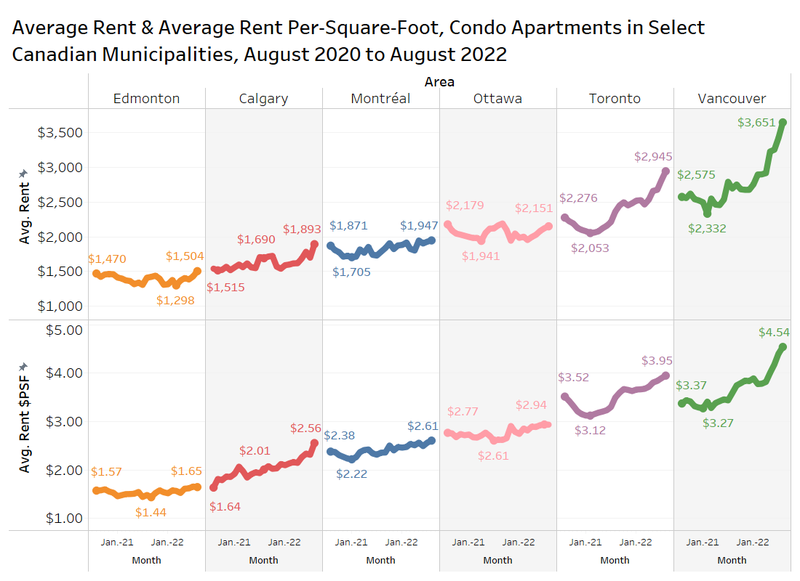

Condo Rental Market Per-Square-Foot

The chart below looks at the average rent per-square-foot by month from December 2018 to December 2021 in Vancouver, Toronto, Mississauga and Ottawa.

The average rent per-square-foot in Vancouver steadily declined throughout 2020 before sharply recovering to the levels experienced at the start of 2019. The average rent per-square-foot hit a low of $3.29 in the early part of 2021 before rising to $3.84 in December 2021.

The average rent per-square-foot in Toronto followed a similar trend, decreasing throughout 2020 to a low of $3.15 before sharply recovering to $3.63 in December 2021.

The average rent per-square-foot in Mississauga did not experience the same levels of decline as Vancouver and Toronto. The price has bounced off a low of $2.64 per-square-foot and has risen to $2.98 per-square-foot in December 2021, which is a market-high level.

In Ottawa, the average rent per-square-foot has generally remained constant, with no clear trends moving in either direction. The average rent per-square-foot has moved from a low of $2.72 to $2.79 in December 2021.

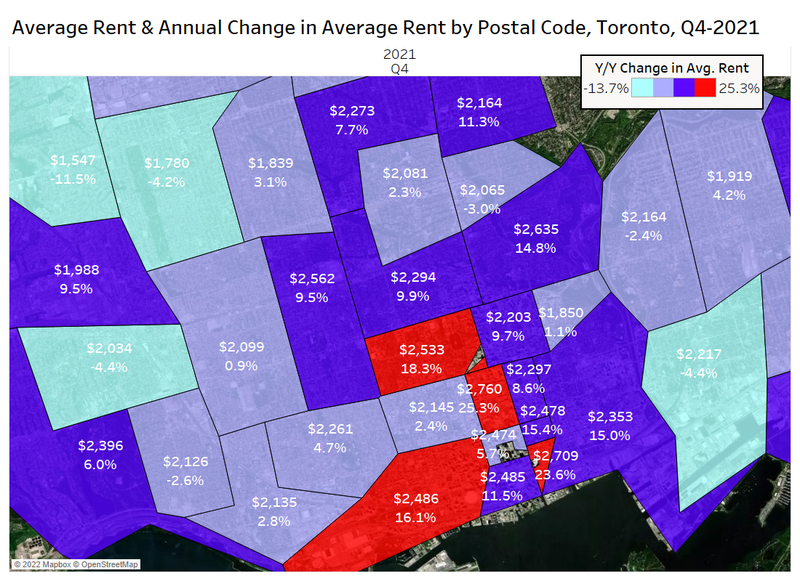

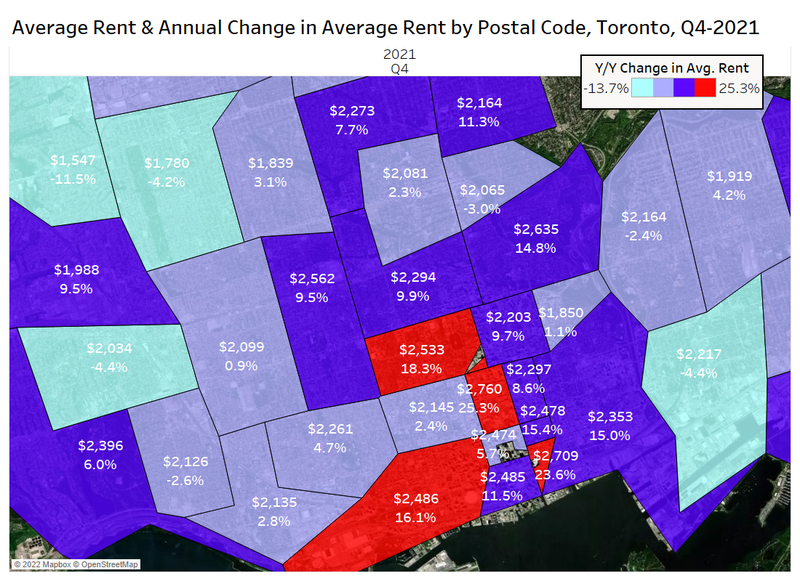

Average Rent by Postal Code in Toronto

The figure below presents the average rent and annual changes in average rent in Toronto by postal code during the fourth quarter of 2021.

In Toronto, the downtown core experienced the highest levels of annual change in average rent, with annual changes ranging from 2.4% to 25%. The high-volume M5V area saw rents increase by 16% annually to $2,486 per month.

The areas of Toronto slightly farther out of the central core generally experienced middling levels of annual change, with many areas experiencing annual changes in average rent ranging from -4% to +4%.

There was clearly a return to prime real estate in the second half of 2021.

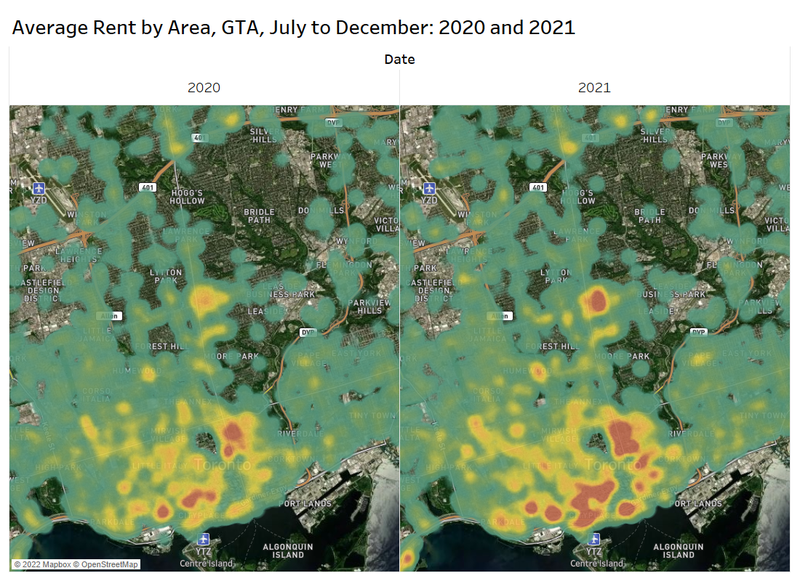

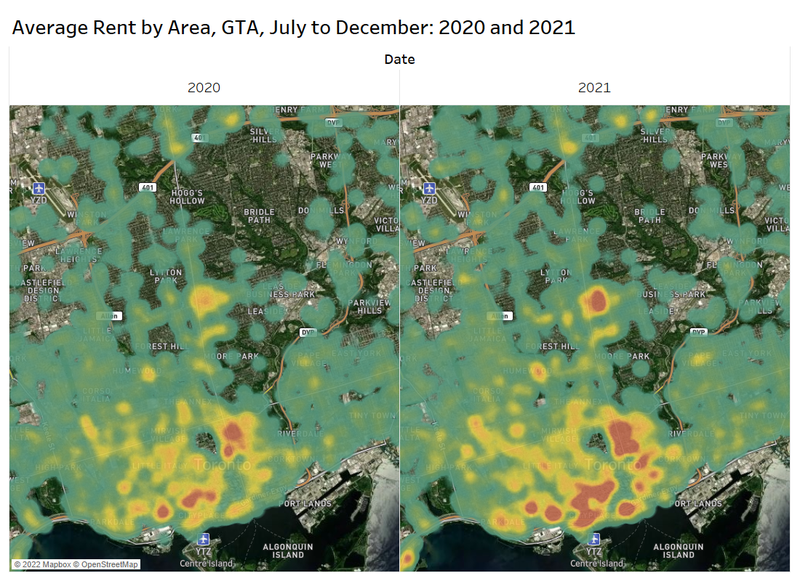

Rental Rates by Area in the GTA

The side-by-side maps below show the average rent by area in the GTA over the final six months of 2020 and the final six months of 2021.

It is clear that the areas with the largest increase in average rent were in the downtown west area, and along Yonge Street near Bloor.

Conclusion

Unlike predictions for 2020, the rent forecasts by Bullpen Research & Consulting and Rentals.ca for 2021 were relatively accurate. The forecasts were within $150 of the average rents for the five selected municipalities. The main exception was Vancouver, where the average rent recovered more sharply than predicted.

After a tumultuous 2020 and 2021, the rental market has posted an annual increase in average monthly rental rates for four months in a row, reinforcing the notion that the rental market is recovering from the sharp 2020 declines. This is most clearly demonstrated by the average per-square-foot rents in Vancouver and Toronto, both declining steadily throughout 2020 and most of 2021 before recovering in the latter half of the year.

Although the real estate market had a strong recovery in the last several months, uncertainty will persist as governments issue further lockdown measures because of the Omicron variant of the COVID-19 virus. There is some consensus among experts that these lockdowns and restrictions will be much shorter than previous ones, so the Bullpen Research & Consulting/Rentals.ca forecast of continued rent growth in most major markets in 2022 has not been altered.

B.C. saw a record number of new homes registered for construction in 2021, but data from the Bank of Canada suggests a significant share of them are likely to be purchased by investors.

The Bank of Canada study looked at mortgage and credit bureau data to determine the percentage of homes in the country being purchased by first-time homebuyers, repeat buyers and investors.

It concluded that investors and repeat buyers make up an increasingly large portion of mortgage-backed home purchases in Canada.

“Home purchases are being driven increasingly by existing homeowners,” the study’s authors write in their conclusion.

“Within this group, investors have seen the largest gain in their share of home purchases during the COVID 19 pandemic.”

Because the study looked at mortgage data, it does not capture homes purchased in cash or by corporations, according to the authors.

The study found first-time buyers made up 47 per cent of the market as of June 1, 2021, down from 53 per cent at the start of 2015.

Meanwhile, the percentage of repeat buyers and investors in the market have both increased. In the study, “repeat buyers” are those who are buying a new home and selling their old one, while “investors” are those who are purchasing a new home and holding onto their old one, often with the goal of renting out one of the properties as a source of income.

Repeat buyers were 33 per cent of the market as of June 2021, up from 30 per cent in January 2015, and investors made up 21 per cent of the market, up from 18 per cent.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, as home sales and prices skyrocketed, purchases by investors grew the most. Investors purchased twice as many homes in June 2021 as they did in June 2020, a 100 per cent increase in the number of purchases.

For repeat buyers, the increase over the same period was 66 per cent, while first time buyers’ purchases grew by 47 per cent.

The Bank of Canada study was published the same week the B.C. government touted a record number of new home registrations in 2021.

“Registered new homes data is collected at the beginning of a project, before building permits are issued, making it a leading indicator of housing activity in B.C.,” the province said in a news release.

The latest numbers from BC Housing show 53,189 new homes were registered in B.C. in 2021. That’s a 67.5 per cent increase from 2020 and the highest yearly total since the provincial housing authority began collecting data on new home registrations in 2002.

The total includes 12,899 purpose-built rentals, a 47.7 per cent increase from the previous year.

B.C. saw a record number of new homes registered for construction in 2021, but data from the Bank of Canada suggests a significant share of them are likely to be purchased by investors.

The Bank of Canada study looked at mortgage and credit bureau data to determine the percentage of homes in the country being purchased by first-time homebuyers, repeat buyers and investors.

It concluded that investors and repeat buyers make up an increasingly large portion of mortgage-backed home purchases in Canada.

“Home purchases are being driven increasingly by existing homeowners,” the study’s authors write in their conclusion.

“Within this group, investors have seen the largest gain in their share of home purchases during the COVID 19 pandemic.”

Because the study looked at mortgage data, it does not capture homes purchased in cash or by corporations, according to the authors.

The study found first-time buyers made up 47 per cent of the market as of June 1, 2021, down from 53 per cent at the start of 2015.

Meanwhile, the percentage of repeat buyers and investors in the market have both increased. In the study, “repeat buyers” are those who are buying a new home and selling their old one, while “investors” are those who are purchasing a new home and holding onto their old one, often with the goal of renting out one of the properties as a source of income.

Repeat buyers were 33 per cent of the market as of June 2021, up from 30 per cent in January 2015, and investors made up 21 per cent of the market, up from 18 per cent.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, as home sales and prices skyrocketed, purchases by investors grew the most. Investors purchased twice as many homes in June 2021 as they did in June 2020, a 100 per cent increase in the number of purchases.

For repeat buyers, the increase over the same period was 66 per cent, while first time buyers’ purchases grew by 47 per cent.

The Bank of Canada study was published the same week the B.C. government touted a record number of new home registrations in 2021.

“Registered new homes data is collected at the beginning of a project, before building permits are issued, making it a leading indicator of housing activity in B.C.,” the province said in a news release.

The latest numbers from BC Housing show 53,189 new homes were registered in B.C. in 2021. That’s a 67.5 per cent increase from 2020 and the highest yearly total since the provincial housing authority began collecting data on new home registrations in 2002.

The total includes 12,899 purpose-built rentals, a 47.7 per cent increase from the previous year.

A real estate sold sign is shown in a Toronto west end neighbourhood May 17, 2020. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Graeme Roy

A real estate sold sign is shown in a Toronto west end neighbourhood May 17, 2020. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Graeme Roy

Macklem has spent the past 18 months explaining that the labour market is too complex to be summed up by those two headline figures. He and his deputies have been using an array of more granular indicators to obtain a more qualitative assessment of the strength of the labour market.

The United States Federal Reserve introduced a similar methodology in the aftermath of the Great Recession, discovering it could keep interest rates lower than it had previously thought without stoking inflation.

Macklem has spent the past 18 months explaining that the labour market is too complex to be summed up by those two headline figures. He and his deputies have been using an array of more granular indicators to obtain a more qualitative assessment of the strength of the labour market.

The United States Federal Reserve introduced a similar methodology in the aftermath of the Great Recession, discovering it could keep interest rates lower than it had previously thought without stoking inflation.

Despite headwinds, most analysts forecast robust housing market this year | Photo: Rob Kruyt

Despite headwinds, most analysts forecast robust housing market this year | Photo: Rob Kruyt

GagliardiPhotography/Shutterstock

GagliardiPhotography/Shutterstock

In Vancouver and Victoria, the average rent for an unfurnished one-bedroom unit is more than $1,800. Meanwhile, the same kind of unit in Toronto is much cheaper at $1,678 per month on average.

Vancouver rent has been climbing in the last six months, reaching a high in December at $1,831.

According to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s 2020 data, the vacancy rate in Victoria is 2.2%.

In Vancouver and Victoria, the average rent for an unfurnished one-bedroom unit is more than $1,800. Meanwhile, the same kind of unit in Toronto is much cheaper at $1,678 per month on average.

Vancouver rent has been climbing in the last six months, reaching a high in December at $1,831.

According to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s 2020 data, the vacancy rate in Victoria is 2.2%.

A new facility would help Ottawa’s swimmers ‘race [their] best race,’ said Alexandre Perreault, seen here at a 2018 competition in China. (Ng Han Guan/The Associated Press)

A new facility would help Ottawa’s swimmers ‘race [their] best race,’ said Alexandre Perreault, seen here at a 2018 competition in China. (Ng Han Guan/The Associated Press)

From left to right, Canada’s Kayla Sanchez, Maggie Mac Neil, Rebecca Smith and Penny Oleksiak celebrate their silver medal at the Tokyo Olympics. Canada’s recent high-profile successes in the pool has made swimming increasingly popular, according to Marcia Morris, president of the Ottawa Sport Council. (Frank Gunn/The Canadian Press)

From left to right, Canada’s Kayla Sanchez, Maggie Mac Neil, Rebecca Smith and Penny Oleksiak celebrate their silver medal at the Tokyo Olympics. Canada’s recent high-profile successes in the pool has made swimming increasingly popular, according to Marcia Morris, president of the Ottawa Sport Council. (Frank Gunn/The Canadian Press)

One of Canada’s “Big Six” banks is declaring next year to be “The Year of The Hike.” National Bank of Canada (NBC) chief strategist (and poet-in-residence) Warren Lovely is calling the first interest rate hike in just a few months. He sees the Bank of Canada (BoC) making its hike in March, way ahead of schedule. Over the next year, the overnight rate is forecast to recoup much of the ground lost during the pandemic. However, Canada’s real estate bubble will prevent it from going much further. Since the country went all-in on housing, it can’t pursue more aggressive policies like healthier economies.

One of Canada’s “Big Six” banks is declaring next year to be “The Year of The Hike.” National Bank of Canada (NBC) chief strategist (and poet-in-residence) Warren Lovely is calling the first interest rate hike in just a few months. He sees the Bank of Canada (BoC) making its hike in March, way ahead of schedule. Over the next year, the overnight rate is forecast to recoup much of the ground lost during the pandemic. However, Canada’s real estate bubble will prevent it from going much further. Since the country went all-in on housing, it can’t pursue more aggressive policies like healthier economies.

A new framework agreement between the federal government and the Bank of Canada announced Monday keeps at its heart a two-per-cent annual inflation rate.However, the central bank will now also consider employment levels and how close they are to the highest level they can reach before fuelling inflation when setting its trendsetting interest rate.

Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland stressed there was no material change to the bank’s marching orders, and that the consideration of employment does not constitute a dual mandate to hit two different targets — a measure that was under consideration for the mandate.The two framed the agreement as codifying the Bank of Canada’s interest in a healthy labour market, something the bank has stressed during the pandemic in explaining its moves.

“Monetary policy works better when people understand it,” Macklem said, “and, really, this agreement clarifies our objectives and it clarifies how we have and can use the flexibility that is built into our framework.”

Under the new agreement, the Bank of Canada may decide to allow inflation to sit closer to either end of the bank’s target range of one to three per cent for short bursts as it determines when the labour market hits its full potential.

It also has flexibility to keep its key interest rate at the lowest level possible for longer stretches to help the economy recover from a downturn.

Since 1991, the Bank of Canada has targeted an annual inflation rate of between one and three per cent, often landing in a sweet spot at two per cent.

Even under those previous mandates, the health of the labour market was a factor in decisions about whether to lower or raise rates, said BMO director of Canadian rates Benjamin Reitzes.

“Case in point, inflation is near five per cent and slack in the labour market has been a key reason why the (Bank of Canada) has kept policy rates at the lower bound,” he wrote in a note.

The Bank of Canada’s key policy rate since the start of the pandemic has been at 0.25 per cent, lowered there to prod spending during the COVID-19 induced downturn and subsequent rebound. As it stands, the bank doesn’t see a rate bump until April 2022 at the earliest.

Changes in the Bank of Canada’s target for the overnight rate influence the prime rates at the country’s big banks that are used as a benchmark for loans such as variable rate mortgages and home equity lines of credit. Changes in the rate may also influence bond yields, which can lead to changes in fixed rate mortgages and other borrowing.

Under the agreement Monday, the central bank said the rate may more often hit rock-bottom and remain there for longer if the bank believes it will help get inflation back on target.

A low-for-longer rate environment may sometimes be needed, the bank said, even if it boosts the likelihood that inflation could overshoot the two per cent target as the economy recovers.

Rate hikes could be more gradual than in the past as the bank figures out if it has properly estimated the full potential of the labour market, meaning that inflation could again rise above the bank’s target.

“This is one reason to think that inflation will, on average, be higher in the coming years than in the past decade, albeit not dramatically so,” said Stephen Brown, senior Canada economist with Capital Economics, noting inflation has averaged 1.7 per cent since the global financial crisis.

The bank noted that figuring out when the country has hit “maximum sustainable employment” may be “impossible” because it can’t be nailed down to one number, and is complicated by a greying workforce and increased digitization.

The bank plans to outline what labour market markers it is monitoring and detail those as part of its regular interest rate announcements.

The deal also outlines how the bank should consider climate change in its policies, although leaving it up to governments to hit emissions targets. “Monetary policy cannot directly tackle the threats posed by climate change,” the statement reads, latter adding that economic modelling should account for its affect on the financial system.

Alex Speers-Roesch with Greenpeace said that on the contrary, central bank policy can assist in fighting climate change. He pointed to the option of the bank buying more environmentally friendly assets, which the Bank of Canada is considering.

A new framework agreement between the federal government and the Bank of Canada announced Monday keeps at its heart a two-per-cent annual inflation rate.However, the central bank will now also consider employment levels and how close they are to the highest level they can reach before fuelling inflation when setting its trendsetting interest rate.

Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland stressed there was no material change to the bank’s marching orders, and that the consideration of employment does not constitute a dual mandate to hit two different targets — a measure that was under consideration for the mandate.The two framed the agreement as codifying the Bank of Canada’s interest in a healthy labour market, something the bank has stressed during the pandemic in explaining its moves.

“Monetary policy works better when people understand it,” Macklem said, “and, really, this agreement clarifies our objectives and it clarifies how we have and can use the flexibility that is built into our framework.”

Under the new agreement, the Bank of Canada may decide to allow inflation to sit closer to either end of the bank’s target range of one to three per cent for short bursts as it determines when the labour market hits its full potential.

It also has flexibility to keep its key interest rate at the lowest level possible for longer stretches to help the economy recover from a downturn.

Since 1991, the Bank of Canada has targeted an annual inflation rate of between one and three per cent, often landing in a sweet spot at two per cent.

Even under those previous mandates, the health of the labour market was a factor in decisions about whether to lower or raise rates, said BMO director of Canadian rates Benjamin Reitzes.

“Case in point, inflation is near five per cent and slack in the labour market has been a key reason why the (Bank of Canada) has kept policy rates at the lower bound,” he wrote in a note.

The Bank of Canada’s key policy rate since the start of the pandemic has been at 0.25 per cent, lowered there to prod spending during the COVID-19 induced downturn and subsequent rebound. As it stands, the bank doesn’t see a rate bump until April 2022 at the earliest.

Changes in the Bank of Canada’s target for the overnight rate influence the prime rates at the country’s big banks that are used as a benchmark for loans such as variable rate mortgages and home equity lines of credit. Changes in the rate may also influence bond yields, which can lead to changes in fixed rate mortgages and other borrowing.

Under the agreement Monday, the central bank said the rate may more often hit rock-bottom and remain there for longer if the bank believes it will help get inflation back on target.

A low-for-longer rate environment may sometimes be needed, the bank said, even if it boosts the likelihood that inflation could overshoot the two per cent target as the economy recovers.

Rate hikes could be more gradual than in the past as the bank figures out if it has properly estimated the full potential of the labour market, meaning that inflation could again rise above the bank’s target.

“This is one reason to think that inflation will, on average, be higher in the coming years than in the past decade, albeit not dramatically so,” said Stephen Brown, senior Canada economist with Capital Economics, noting inflation has averaged 1.7 per cent since the global financial crisis.

The bank noted that figuring out when the country has hit “maximum sustainable employment” may be “impossible” because it can’t be nailed down to one number, and is complicated by a greying workforce and increased digitization.

The bank plans to outline what labour market markers it is monitoring and detail those as part of its regular interest rate announcements.

The deal also outlines how the bank should consider climate change in its policies, although leaving it up to governments to hit emissions targets. “Monetary policy cannot directly tackle the threats posed by climate change,” the statement reads, latter adding that economic modelling should account for its affect on the financial system.

Alex Speers-Roesch with Greenpeace said that on the contrary, central bank policy can assist in fighting climate change. He pointed to the option of the bank buying more environmentally friendly assets, which the Bank of Canada is considering.

In the second half of this year, condo developers were confident enough to launch new projects in Vancouver, reasoning that the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic is in the rear-view mirror, and absorption has been robust enough to ensure launches continue through next year.

“In some cases with the projects we oversaw at BakerWest, some were sold out within the first month, and all of them were sold out in a two- to three-month period, and this trend will definitely continue as there isn’t enough supply,” Chan said, adding that could change depending on the area. “Vancouver, its downtown, north shore, Richmond and the Fraser Valley service different purposes, and different price points exist in different municipalities.”

Indeed, the multiplicity of municipalities reflects a variance of demand cycles. From Abbotsford to the Tri-Cities — Coquitlam, Port Coquitlam, Port Moody, and the villages of Anmore and Belcarra — supply is lagging far behind demand, Jamie Squires, Senior Vice President and Managing Broker of Fifth Avenue Real Estate Marketing, says.

In the second half of this year, condo developers were confident enough to launch new projects in Vancouver, reasoning that the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic is in the rear-view mirror, and absorption has been robust enough to ensure launches continue through next year.

“In some cases with the projects we oversaw at BakerWest, some were sold out within the first month, and all of them were sold out in a two- to three-month period, and this trend will definitely continue as there isn’t enough supply,” Chan said, adding that could change depending on the area. “Vancouver, its downtown, north shore, Richmond and the Fraser Valley service different purposes, and different price points exist in different municipalities.”

Indeed, the multiplicity of municipalities reflects a variance of demand cycles. From Abbotsford to the Tri-Cities — Coquitlam, Port Coquitlam, Port Moody, and the villages of Anmore and Belcarra — supply is lagging far behind demand, Jamie Squires, Senior Vice President and Managing Broker of Fifth Avenue Real Estate Marketing, says.

New build presales have spiked in Surrey City and North Delta with 2,543 high-rise sales, 1,071 low-rise sales, and 626 new townhouse sales. Squires noted that few immigrants have arrived in Canada during the pandemic, yet sales have been persistently elevated because, in addition to buyers within the province, BC real estate has gotten a lot of attention from purchasers wanting to flee dreaded Prairie winters. And as the pandemic appears to be waning and more newcomers start arriving in the country, demand is set to arise again in 2022, albeit by only 2-3%, Squires estimates.

“The biggest issue now is a clear lack of supply, so as long as the government does something to push cities and municipalities to be more accountable to approval times, I don’t see a huge influx of supply happening to stabilize this market,” she said.

Kelowna is experiencing unprecedented presale absorption, according to Scott Brown, Development and Marketing Lead for BC at Peerage Realty Partners West, because, unlike in the aftermath of the Great Recession when urban cores generally rebounded before suburbs, the coronavirus has created conditions for an obverse recovery this time around.

“In Kelowna, Victoria, and you could argue Kamloops is a third, prices have gone up significantly,” Brown said, ”but you could still find a wood frame project in downtown Kelowna for $600-800 per square foot. Kelowna is attractive to younger and older people moving out of Vancouver because they’re getting price appreciation there. Langford, Kelowna, Greater Victoria and the Okanagan are driven by the exodus of higher density areas of BC, like Vancouver, and the older buyers want to live in smaller, less busy cities, while a significant amount of young people are flexible with their work arrangements and are choosing to enter those markets because they can still afford a home and work remotely.”

New build presales have spiked in Surrey City and North Delta with 2,543 high-rise sales, 1,071 low-rise sales, and 626 new townhouse sales. Squires noted that few immigrants have arrived in Canada during the pandemic, yet sales have been persistently elevated because, in addition to buyers within the province, BC real estate has gotten a lot of attention from purchasers wanting to flee dreaded Prairie winters. And as the pandemic appears to be waning and more newcomers start arriving in the country, demand is set to arise again in 2022, albeit by only 2-3%, Squires estimates.

“The biggest issue now is a clear lack of supply, so as long as the government does something to push cities and municipalities to be more accountable to approval times, I don’t see a huge influx of supply happening to stabilize this market,” she said.

Kelowna is experiencing unprecedented presale absorption, according to Scott Brown, Development and Marketing Lead for BC at Peerage Realty Partners West, because, unlike in the aftermath of the Great Recession when urban cores generally rebounded before suburbs, the coronavirus has created conditions for an obverse recovery this time around.

“In Kelowna, Victoria, and you could argue Kamloops is a third, prices have gone up significantly,” Brown said, ”but you could still find a wood frame project in downtown Kelowna for $600-800 per square foot. Kelowna is attractive to younger and older people moving out of Vancouver because they’re getting price appreciation there. Langford, Kelowna, Greater Victoria and the Okanagan are driven by the exodus of higher density areas of BC, like Vancouver, and the older buyers want to live in smaller, less busy cities, while a significant amount of young people are flexible with their work arrangements and are choosing to enter those markets because they can still afford a home and work remotely.”

As a result, Brown anticipates 2022 will be a very strong year for home sales in the province, although perhaps the pace won’t be as torrid as has been in 2021. Brown also believes the rapid pace of appreciation will stabilize by next year, but if it exceeds this year’s pace, it will not be by much.

“It will either be a little over or a little less because of the chronic undersupply.”

Victoria has one of Canada’s most expensive real estate markets, and although sales declined by 24.7% year-over-year in October, it doesn’t tell the whole story. According to internal data from

As a result, Brown anticipates 2022 will be a very strong year for home sales in the province, although perhaps the pace won’t be as torrid as has been in 2021. Brown also believes the rapid pace of appreciation will stabilize by next year, but if it exceeds this year’s pace, it will not be by much.

“It will either be a little over or a little less because of the chronic undersupply.”

Victoria has one of Canada’s most expensive real estate markets, and although sales declined by 24.7% year-over-year in October, it doesn’t tell the whole story. According to internal data from  Source: Statistics Canada, Haver, RBC Economics

Source: Statistics Canada, Haver, RBC Economics

Over five decades, the country’s growth has been anything but dynamic. Real economic growth rates fell from an average of 4.1% in the 1970s to 2.1% between 2010 and 2019. Should we carry on our existing course, we expect a return to a sluggish trend growth of around 1.8% per year beyond 2023, a record reflective of slow labour force growth and muted productivity.

Canada isn’t alone. Many other advanced economies have experienced the same deceleration, attributed to a greying population, the slowing pace of innovation, and in some cases, post-recessionary economic scarring. The trend has been stubborn, suggesting that underlying structural issues will continue to be a powerful force now and into the future.

Over five decades, the country’s growth has been anything but dynamic. Real economic growth rates fell from an average of 4.1% in the 1970s to 2.1% between 2010 and 2019. Should we carry on our existing course, we expect a return to a sluggish trend growth of around 1.8% per year beyond 2023, a record reflective of slow labour force growth and muted productivity.

Canada isn’t alone. Many other advanced economies have experienced the same deceleration, attributed to a greying population, the slowing pace of innovation, and in some cases, post-recessionary economic scarring. The trend has been stubborn, suggesting that underlying structural issues will continue to be a powerful force now and into the future.

Increased digitization and automation should boost productivity, data and product development. And digitization—together with a greying population that tends to consume more services—can create opportunities for expanded services trade. Investment is needed for decarbonization, mitigation, and development of new green technologies. These same shifts in the global economy can bring opportunities for Canadian firms to export products and expertise, earning global incomes that can help fund the domestic adjustment to the new economy—one with greater spending, investment, innovation and growth.

Getting there will mean tackling new economy challenges, including changing sources of economic value that risk capital obsolescence and loss of competitiveness. It will mean responding to shifts in skills and jobs that threaten displaced workers, and inequality. It will also mean reckoning with where we have not performed well in the past.

Increased digitization and automation should boost productivity, data and product development. And digitization—together with a greying population that tends to consume more services—can create opportunities for expanded services trade. Investment is needed for decarbonization, mitigation, and development of new green technologies. These same shifts in the global economy can bring opportunities for Canadian firms to export products and expertise, earning global incomes that can help fund the domestic adjustment to the new economy—one with greater spending, investment, innovation and growth.

Getting there will mean tackling new economy challenges, including changing sources of economic value that risk capital obsolescence and loss of competitiveness. It will mean responding to shifts in skills and jobs that threaten displaced workers, and inequality. It will also mean reckoning with where we have not performed well in the past.

Meantime, lagging innovation could soon present an even greater problem. As technology advances, more economic value will be encapsulated in data, algorithms, brands, digital services and other ‘intangible assets’. With these assets being more scalable compared to tangible inputs like physical capital and labour, delivering large gains to its developers and owners, economic prosperity will increasingly depend on our transition to an innovation economy. And while innovation and competitiveness are influenced by many factors, from policy and demographics to the external environment, business investment is essential.

Meantime, lagging innovation could soon present an even greater problem. As technology advances, more economic value will be encapsulated in data, algorithms, brands, digital services and other ‘intangible assets’. With these assets being more scalable compared to tangible inputs like physical capital and labour, delivering large gains to its developers and owners, economic prosperity will increasingly depend on our transition to an innovation economy. And while innovation and competitiveness are influenced by many factors, from policy and demographics to the external environment, business investment is essential.

To varying degrees, Canada performs well in international rankings for entrepreneurial ambition, market sophistication, venture capital financing, institutions, and a skilled workforce. But it ranks poorly in other innovation inputs, with low business R&D investment, low adoption of information communications technology, low per capita scientific activity, an inadequate IP regime, and low openness to competition. And Canada has had trouble translating inputs to innovation outputs. It has middling patent activity, low business creation, and difficulty scaling businesses into global exporters. Firms that are able to export globally are a signal of economic competitiveness, yet net exports have been a drag on economic growth in Canada for much of the past two decades.

The result is imbalanced economic growth. When balanced, growth is derived from multiple sectors of the economy—consumption, investment, and net exports. For Canada, the imbalance between the low growth contribution from net exports and business investment on one side versus high contributions from consumption and housing on the other, means the economy is more exposed to individual economic shocks. For example, a shock to the housing sector could directly reduce economic growth through less construction and sales, and potentially force an abrupt, costly reallocation of resources to other sectors. With climate actions and trade tensions darkening prospects for Canada’s biggest export—crude oil—this imbalance could get worse.

To varying degrees, Canada performs well in international rankings for entrepreneurial ambition, market sophistication, venture capital financing, institutions, and a skilled workforce. But it ranks poorly in other innovation inputs, with low business R&D investment, low adoption of information communications technology, low per capita scientific activity, an inadequate IP regime, and low openness to competition. And Canada has had trouble translating inputs to innovation outputs. It has middling patent activity, low business creation, and difficulty scaling businesses into global exporters. Firms that are able to export globally are a signal of economic competitiveness, yet net exports have been a drag on economic growth in Canada for much of the past two decades.

The result is imbalanced economic growth. When balanced, growth is derived from multiple sectors of the economy—consumption, investment, and net exports. For Canada, the imbalance between the low growth contribution from net exports and business investment on one side versus high contributions from consumption and housing on the other, means the economy is more exposed to individual economic shocks. For example, a shock to the housing sector could directly reduce economic growth through less construction and sales, and potentially force an abrupt, costly reallocation of resources to other sectors. With climate actions and trade tensions darkening prospects for Canada’s biggest export—crude oil—this imbalance could get worse.

Source: Bloomberg, RBC Economics | *data to November 1, 2021

Source: Bloomberg, RBC Economics | *data to November 1, 2021

Having the right number of workers is key, but skills are just as important. If graduating youth are equipped with new skills and starting in new fields, the impact of potential displaced workers could be minimized. But some educational programs are not keeping pace with change, access to work integrated learning can be uneven, and young people can struggle to get hold of the information they need to make career choices. Despite greater demands, post-secondary institutions face a constrained funding model with tuition freezes and reliance on high-paying international students.

Mid-career workers face different challenges. While tight labour markets should incentivize more business spending on employee training, low wage workers whose jobs are more likely to be affected by automation, and who could benefit the most from upskilling, are also the least likely to participate in it.

Having the right number of workers is key, but skills are just as important. If graduating youth are equipped with new skills and starting in new fields, the impact of potential displaced workers could be minimized. But some educational programs are not keeping pace with change, access to work integrated learning can be uneven, and young people can struggle to get hold of the information they need to make career choices. Despite greater demands, post-secondary institutions face a constrained funding model with tuition freezes and reliance on high-paying international students.

Mid-career workers face different challenges. While tight labour markets should incentivize more business spending on employee training, low wage workers whose jobs are more likely to be affected by automation, and who could benefit the most from upskilling, are also the least likely to participate in it.

But these relationships aren’t guaranteed, especially if social spending only finances current consumption, doesn’t target the largest equity gaps, or discourages employment. And financing government programs with a deficit comes with a risk: the new spending might not lead to sufficient economic growth to address future interest rate increases or other economic shocks.